I’ve been thinking about war a lot lately.

The war in Ukraine, of course. But also, what is it about war that turns people into savages, that makes them commit horrors they never would have dreamed of in real life?

One Paris memorial raises that question more movingly than any other: the Jardin mémorial des enfants du Vél’ d’Hiv’. Before I translate that, let me tell you who it’s for.

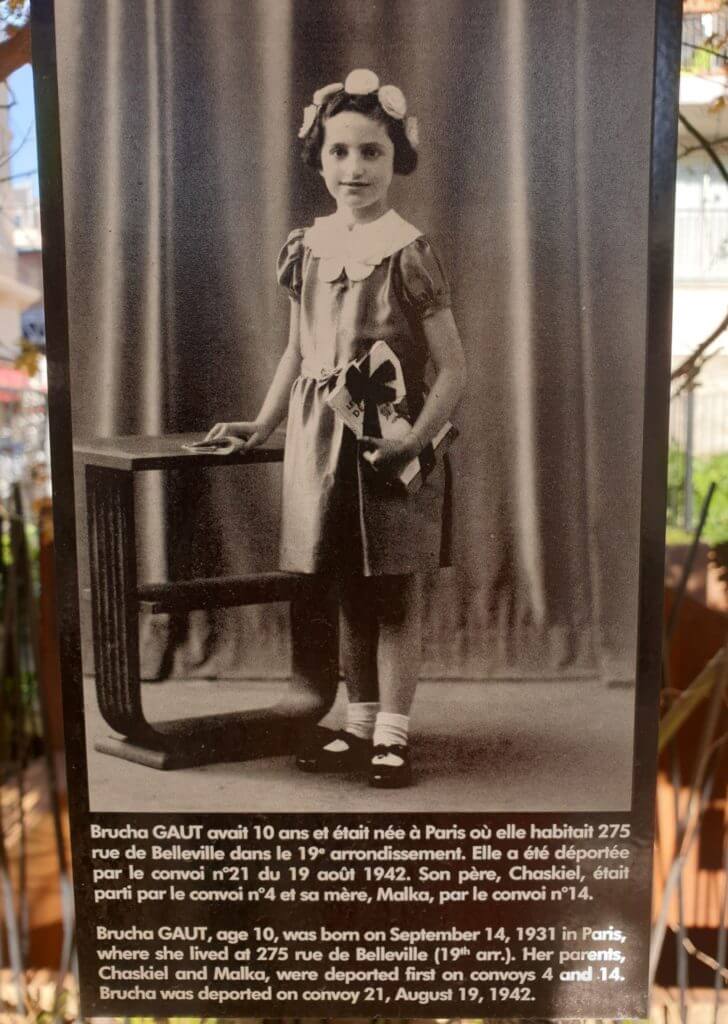

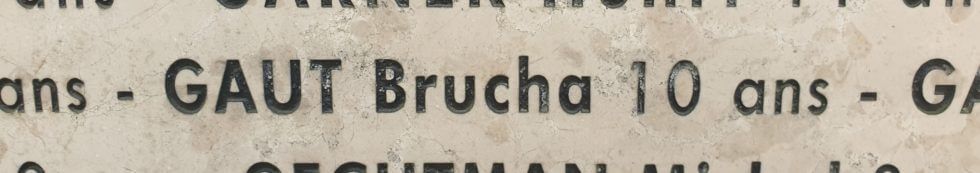

It’s for Brucha Gaut, who at the age of 10 was deported from Paris on August 19, 1942, on a cattle car to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Her parents had been sent away earlier.

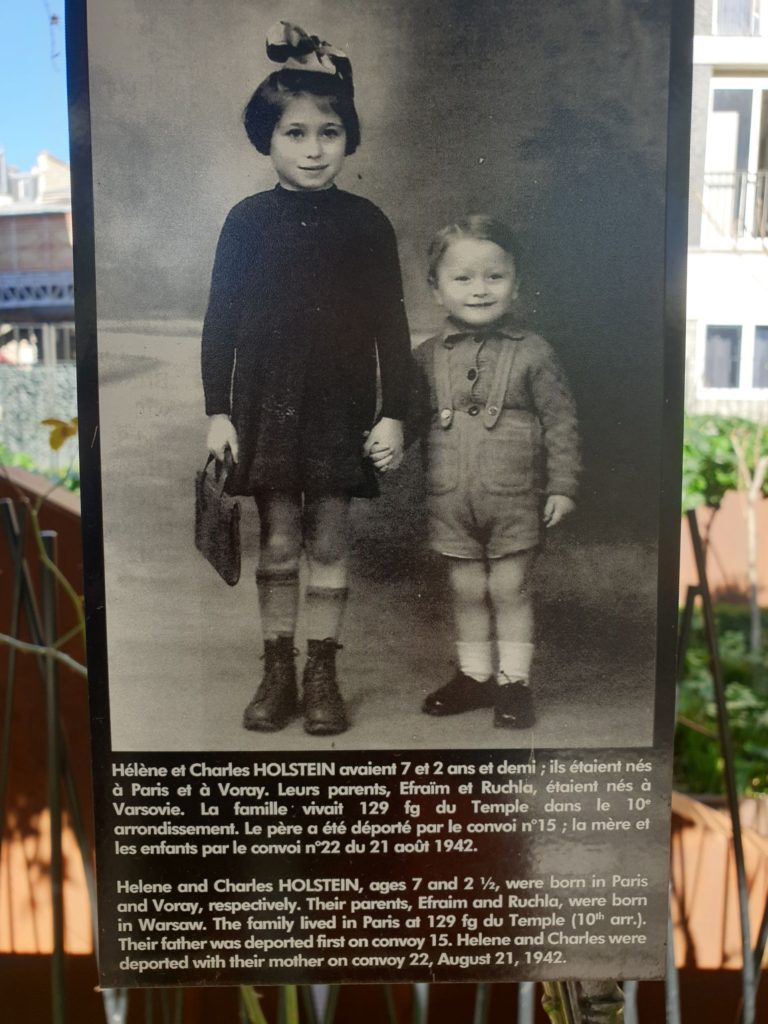

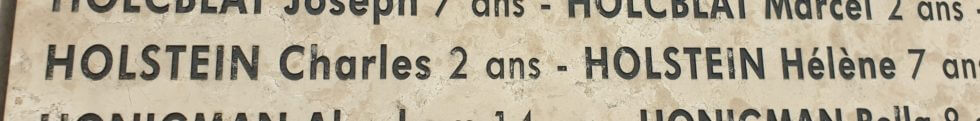

It’s for Hélène and Charles Holstein, who at ages 7 and 2 1/2 were sent to Auschwitz on Aug. 21, 1942. They were with their mother, but their father had already been taken away.

It’s for Paulette Zajac, who was similarly deported with her mother on August 17, 1942.

They, and the rest of the 4,115 children honored in this tiny garden near the Eiffel Tower, all were arrested and taken from their homes on July 16 and 17, 1942, by French police acting at the behest of the occupying Nazis. They were all Jewish.

More than half of the 13,000 or so people deported in this roundup were initially taken to a Paris sports arena called the Vélodrome d’Hiver (Winter Stadium). For days and weeks, they were held there, families often separated, with almost no food, water or bathrooms. Then they were loaded on buses and taken to such internment camps as Drancy, just north of Paris, and put on trains east. With a handful of exceptions, they all died in the camps.

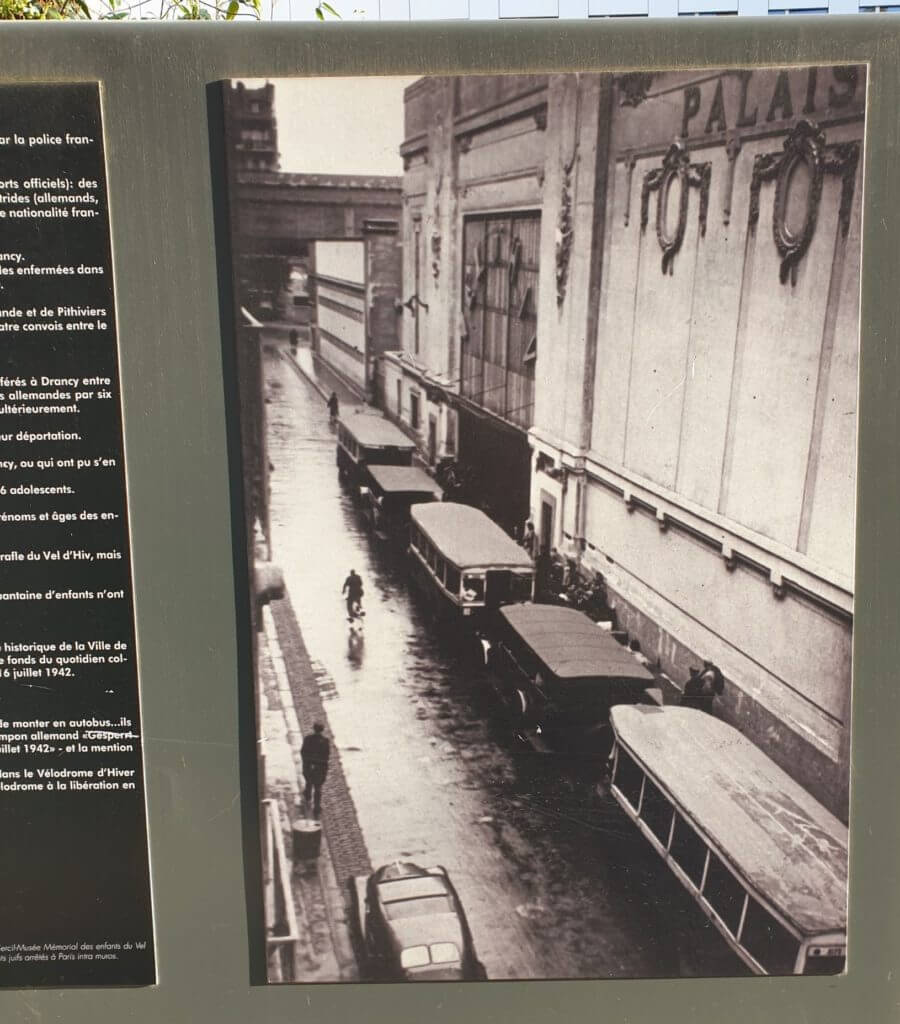

The memorial garden is located on the site of the Vel d’Hiv, as the sports facility was called. It was inaugurated on July 16, 2017, the 75th anniversary of the roundups. Before that, there was only a plaque on a nearby building (the stadium itself was demolished in 1959 after a fire). Only one photo exists of the buses loading arrestees at the stadium.

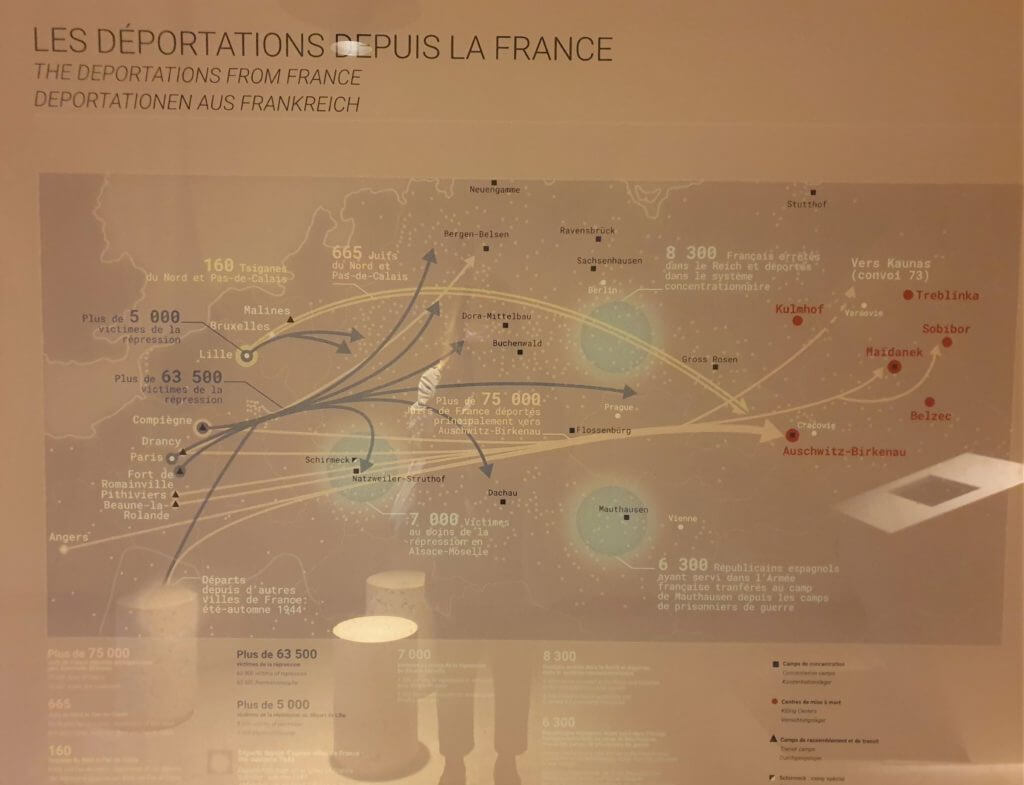

In all, more than 76,000 Jews were sent from France to the camps, almost always by French police, at a time when the puppet government of Vichy exercised control in the Nazi-occupied north as well as the south.

Many of the deportees had already fled the Nazi invasions of Eastern Europe, and in fact the cover story by such officials as government head Pierre Laval was that the foreigners had to be sacrificed to save French foreigners had to be sacrificed to save French Jews. Except that many of the children, having been born in France, were French.

Paris has other memorials to deportations.

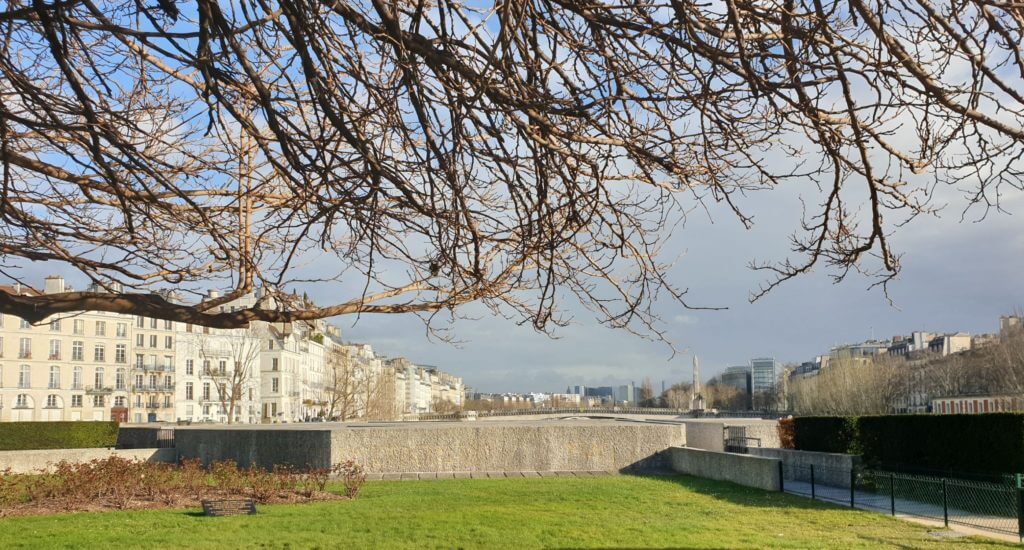

Not far from the children’s garden, along the Seine, is a statue commemorating the martyrs.

The official government memorial to deportees is at the very east end of the Ile de la Cité, just behind the Notre Dame reconstruction. There are some decent exhibits inside the subterranean museum, but the outside screams Don’t Enter Here.

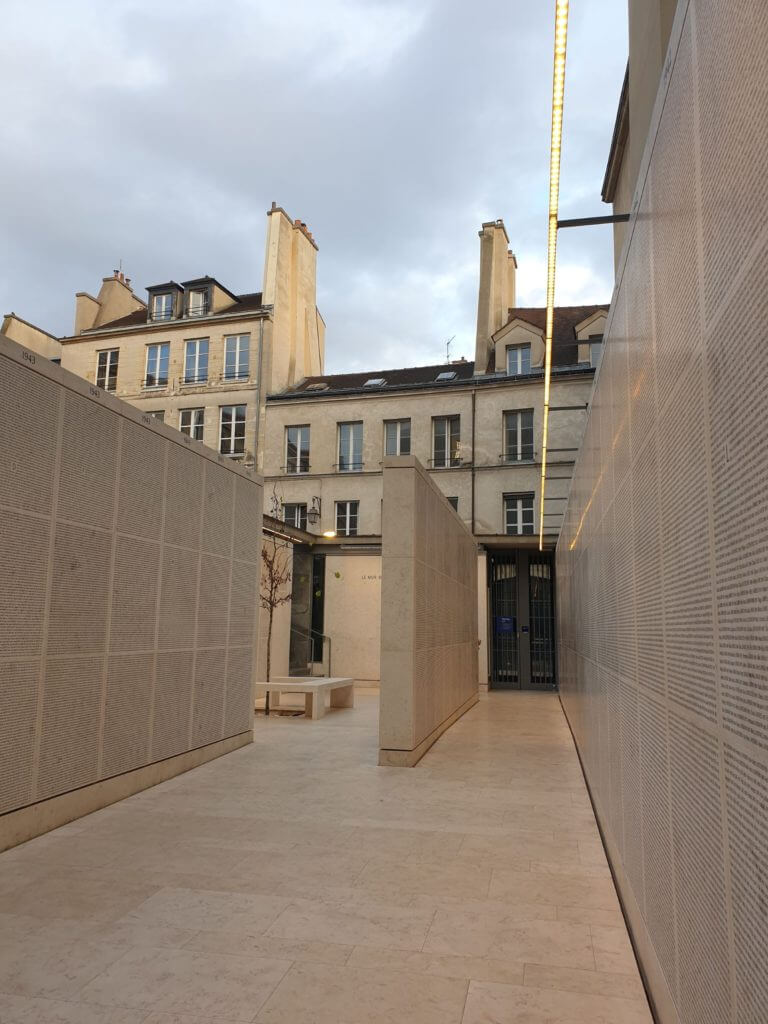

Not far away, on the Right Bank, is the Memorial de la Shoah which, like the children’s garden, focuses on identifying and naming the victims. It also includes the secret police files kept on Jews in France. Most moving to me is that it is located in the Marais district, where many Jews lived and were taken from. I wondered if the houses across the street were among such places.

In fact, commemorative signs and plaques are everywhere in Paris, especially in front of schools.

More children.

But my thoughts, and footsteps, keep returning to the garden, on the rue Nélaton. It’s an inviting place, in a strange way.

The photos of the children are posted on two sides, and there’s a statue in the corner. You can sit on little concrete stools and look at the wall. That is where I tried to think about what could make someone, anyone, do this to children.

The photos of the children are posted on two sides, and there’s a statue in the corner. You can sit on little concrete stools and look at the wall. That is where I tried to think about what could make someone, anyone, do this to children.

My watchwords in writing this blog have been to write what I see and what I know. Those two ideas have allowed me to dare to write about a country I understand only imperfectly, rather than making assumptions or generalizing. I’ve tried to avoid commentary, at least the off-the-cuff, non-observational kind. Now, I want to express an opinion, a strong opinion. But I don’t have the words.

So I will close with the words of Serge Klarsfeld, the 86-year-old activist and Nazi hunter who, with his wife Beate, fought to bring these atrocities to light, including before 1995, when the French government was unwilling to face its past. He was a key driver of the garden for the Vel d’Hiv children, whose inauguration he attended with President Emmanuel Macron and then-Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

So I will close with the words of Serge Klarsfeld, the 86-year-old activist and Nazi hunter who, with his wife Beate, fought to bring these atrocities to light, including before 1995, when the French government was unwilling to face its past. He was a key driver of the garden for the Vel d’Hiv children, whose inauguration he attended with President Emmanuel Macron and then-Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

“The simple fact of delivering these thousands of children to the Nazi occupiers, and separating them from their parents by deporting them in extreme distress, is for Vichy France complicity in a crime against humanity and genocide,” he said at the ceremony.

Let’s hope those words never have to be spoken about the period we are in now.

Comment (0)